The ACI allows for a broad range of trade and investment-related response measures that could have far-reaching consequences, particularly for third-country businesses. However, adoption of such measures is the outcome of a lengthy decision-making process, involving both the European Commission (Commission) and the EU Member States through the Council of the EU (Council), that could take several months.

To allow companies to anticipate the ACI’s potential deployment, this legal update provides a concise overview of the ACI: its scope, deployment thresholds and procedures, the EU’s response toolbox (including potential targeting of multinationals with or without an EU presence), and potential avenues for challenge.

What the ACI does

The ACI (Regulation (EU) 2023/2675) provides a framework to deter, counter and obtain reparation for “economic coercion” by third countries. The EU may investigate alleged coercion, seek cessation and reparation through engagement and international avenues. If those efforts fail, the ACI allows for the imposition of “response measures” targeting trade in goods, trade in services, public procurement, investment, IP, capital markets and other financial services.

The ACI reflects the EU’s shift towards “open strategic autonomy” and economic security. Amid heightened geopolitical competition and incidents perceived as coercion (e.g., Sino-Lithuanian relations), the EU sought a structured, EU-wide mechanism to deter coercive tactics and respond in a coordinated way that raises the sender state’s costs.

When it applies

Deployment requires a legal and factual assessment that three cumulative conditions are met:

- A third country has taken, or threatens, action impacting trade or investment.

- The action aims to influence an EU or Member State decision to adopt, amend, or withdraw a particular act.

- The influence would interfere with legitimate sovereign choices of the EU or a Member State.

When assessing whether these conditions are met, the Commission and the Council considers qualitative and quantitative indicators such as the nature and scale of impact on trade or investment, and whether the third country invokes a recognised legitimate concern. The definition is intentionally broad to allow case-by-case judgments.

How it proceeds

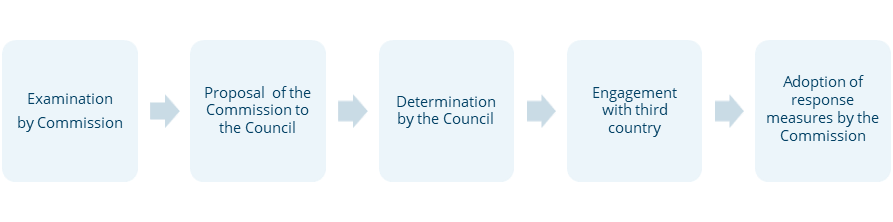

The process has two phases. First, the Commission investigates and, if conditions are met, proposes that the Council determine the existence of coercion and seek its cessation or reparation. The Council decides by qualified majority (at least 55% of Member States (currently 15), representing 65% of the EU population). Second, the Commission engages the third country (negotiation, mediation, conciliation, World Trade Organization or other fora). If coercion persists or reparation is not obtained, the Commission adopts an implementing act with response measures under the “examination procedure”, which effectively allows Member States to block proposed response measures. Measures are reviewable and can be suspended or terminated if coercion ceases, reparation is provided, or the EU’s interests so require.

The ACI only sets indicative timelines: four months for the Commission’s examination and six months for the investigation into whether response measures should be adopted. Timing will mainly depend on Council dynamics and the engagement phase. Once preconditions are met, the Commission can move relatively swiftly to adopt an implementing act setting out response measures, provided that the implementing act does not face any hurdles by Member States under the examination procedure.

What measures look like and how they are selected

Annex I of the ACI provides a wide toolbox for response measures:

| Category 1 | Imposition of new or increased customs duties, including those exceeding the MFN level |

| Category 2 | Introduction or increase of import and export restrictions or payment restrictions for goods |

| Category 3 | Introduction of trade restrictions affecting transit or internal measures for goods |

| Category 4 | Measures affecting participation in public procurement, including exclusion of goods, services or suppliers and score adjustments following evaluation |

| Category 5 | Measures affecting trade in services |

| Category 6 | Measures affecting access to the Union for foreign direct investment (FDI) |

| Category 7 | Restrictions on intellectual property rights or the commercial exploitation by nationals of third countries |

| Category 8 | Restrictions on banks, insurers, capital markets and other financial services |

| Category 9 | Introduction or expansion of restrictions on goods under the Union’s chemical regulation |

| Category 10 | Introduction or expansion of restrictions on goods under the Union’s sanitary and phytosanitary regulation |

Selection of response measures to counter economic coercion must be effective, proportionate to the injury, minimise undue harm to the EU, be administratively feasible and respect international law. The Commission will typically calibrate measures to the trade or investment value impacted and consider EU dependence on affected goods, services and investments.

In practice, the EU may rely less on broad tariffs and export bans under the ACI if other faster instruments are available. For instance, in response to certain US tariff measures, the EU adopted a package of retaliatory tariffs and export restrictions under another instrument (Regulation (EU) No 654/2014). These were suspended as a result of the US-EU framework on an agreement on reciprocal, fair and balanced trade.

The Commission may complement the ACI with measures adopted under other EU legal frameworks, such as those governing Union funding or participating in research and innovation programmes. It must coordinate these actions with any ACI measures to ensure a coherent and proportionate overall EU response that does not exceed the injury inflicted on the EU.

Who can be targeted

Measures may be of general application by sector, region or operator, or be specific to designated persons “connected or linked” to a third‑country government and engaged in certain trade or FDI‑related activities.

The ACI’s nationality rules determine the origin of goods by non‑preferential origin rules. A legal person is “of” a third country under the ACI when the nationality of the relevant service or investment is attributed to that country. For services supplied without an EU commercial presence, nationality follows the country of incorporation where the entity also conducts substantive business operations. For services supplied through an EU establishment, a two‑step test applies: if the EU establishment has substantive business operations that give it a direct and effective link to the Member State economy, its nationality is that Member State unless Union response measures target it, if it lacks such substantive operations, nationality follows the origin of those who own or control the entity. The same approach applies to determining the nationality of direct investments. As a result, EU‑incorporated subsidiaries of third‑country groups may be treated as “of” that third country, especially where they lack substantive business operations or to prevent circumvention.

Business implications

- Non-EU companies could face supply limits due to EU export restrictions or constrained cross-border services. Under the ACI, export restrictions can apply to goods subject to export controls. For example, certain advanced lithography machinery produced by Netherlands-based ASML is subject to export controls, and its export could potentially be restricted.

- Non-EU companies engaged in certain trade or FDI‑related activities could face individually targeted measures if “connected or linked” to a third-country government.

- Non-EU companies without an EU commercial presence may be exposed to border-facing and cross-border measures. These may include additional tariffs, quotas, or export bans to the EU; denial or restriction of market access in specified service sectors when supplied cross-border; exclusion from EU public procurement; and limits on the provision of EU financial services.

- Non-EU companies with an EU commercial presence may face both border-facing measures and establishment-related constraints. These could include procurement exclusions for EU subsidiaries or authorisation or licensing conditions in regulated sectors.

Legal challenge avenues

At EU level, the ACI’s deployment could be challenged directly before the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) by an action for annulment against the Commission’s implementing act imposing response measures. Standing to bring such a challenge will depend on the extent to which a company is concerned by the response measures. Companies that are named and individually designated in a response measure should, in principle, have standing to bring such a challenge. A successful challenge could result in whole or partial annulment of the implementing act.

If the response measures entail national implementing measures that can be challenged before a national court of an EU Member State, the EU response measures could also be challenged indirectly before those national courts. National courts could make preliminary references to the CJEU on the ACI’s interpretation and the validity of response measures.